The main geothermal power station in Iceland is starting to draw heat from hell. In the North of Iceland, the Crater Hell, or Víti to the natives, portrays running water near glowing magma.

The geothermal area in the north was always a feasible option for the Icelanders to utilize the vast energy resources, lying deep in the midst of the melting hot lava. But for a long time many doubted whether Krafla would ever actually enter operation, when large-scale volcanic eruptions started only two kilometres away from the station, posing a serious threat to its existence. Work continued, however, and the station went on stream early in 1977.

The crater erupted in 1724 and the eruption lasted for 5 years. The last eruption was a small one which lasted for nine years, between 1975 and 1984.

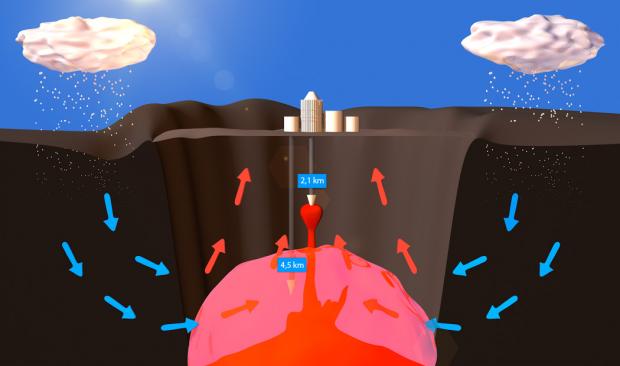

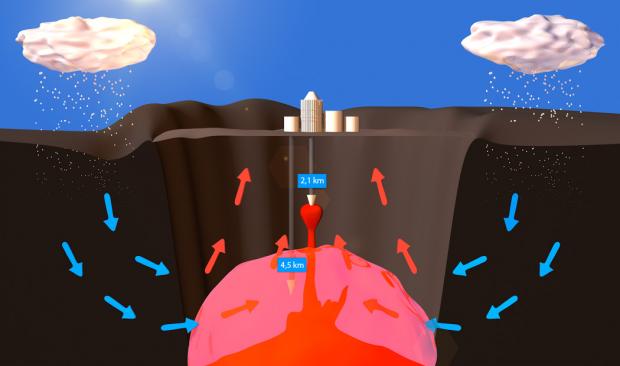

The area will erupt again, but Icelandic scientists have drilled a two-kilometer deep well into the crater to judge opportunities for utilizing this deep geo-energy.

“This is the hottest production well in the world, with a temperature of 450° C and a pressure of 140 bars, in other words about 140 times that of normal air pressure at sea level,” says Guðmundur Ómar Friðleifsson, who heads the project, to Science Nordic.

The Icelanders are trying a novel and bold technology before the next eruption occurs. They are drilling as close to the magma chamber as they can. Here they will extract from five to ten times the energy they currently get from the drill holes that serve the power plant.

In the vicinity of the magma, ground water is so hot and compressed that it is no longer a mixture of water and steam, but rather a superheated dry steam. This superheated steam can liberate more energy than normal steam driving the turbines that convert it into electricity.

Following a failed attempt at drilling deep further from the volcano, IDDP decided to drill right at Krafla, but not without making thorough preparations. Drilling of the well dubbed IDDP-1 started in March 2009. Iceland was then in the midst of its worst ever economic crisis but work continued nevertheless.

Initially everything went according to plan. Then the troubles started. The drill string got stuck and was twisted off. New holes had to be drilled next to the old one. Delays ran into weeks.

Nor could the engineers drill the first and widest well down to 2,400 metres as planned. They decided to call it quits at a depth of 1,958 metres. This proved fortunate because soon all their problems were clear – as glass.

The last rock they’d reached was solidified natural glass, obsidian. The engineers had drilled right into a pocket of melted rock – into magma. Geologists calculated the thickness of this pocket at 50 metres or more in order to have remained in a molten state inside the cooler rock ever since the magma chamber formed in the 1970s and ’80s.

The obsidian created a 20-metre glass stopper in the bottom of drill hole IDDP-1. The engineers pumped cold water into the hole and the rock heated it up for months. This allowed them to appraise the heat flow.

“We are still measuring the heat conduction from the well,” says Friðleifsson, who has managed IDDP since the beginning of 2000.

Even though IDDP-1 is the hottest production well on the planet and the water is superheated, it has less pressure and heat than the scientists and engineers behind the IDDP originally hoped to reach beneath Krafla.

“The well IDDP-1 will produce from 25 to 35 megawatts. This is about half of what the entire rest of the Krafla power plant currently generates. Landsvirkjun is now planning to use steam from this well in power production by year’s end,” says Friðleifsson.

Sources

Science Nordic

Landsvirkjun