Various characteristics of Icelandic economy seem to confirm the fact, that an affluent society, where the GDP per capita in 2007 was $66,240.30, is heavily dependent on the fisheries. According to recent analysis, export of fish products in foreign trade, account for around 75% of all marine goods export in Iceland and 50% of the foreign exchange income from marine goods in general.

Various characteristics of Icelandic economy seem to confirm the fact, that an affluent society, where the GDP per capita in 2007 was $66,240.30, is heavily dependent on the fisheries. According to recent analysis, export of fish products in foreign trade, account for around 75% of all marine goods export in Iceland and 50% of the foreign exchange income from marine goods in general.

Following these statistics, it was found out that the total, direct and indirect fisheries’ contribution is estimated to be within the borders of 40% – 45% of GDP and might differ around 5% by looking at different sources. Using other words, without the fishery based economy, Icelandic GDP would be estimated as 60% of the current one. However, not only the state’s economy is strongly based on fisheries.

The analysis must take into account, that the fisheries determine the major of citizens personal, individual income and income distribution, and what is more, in some part of Iceland as for instance West Fiords, around Husavik or Ólafsfjordur and many others, they are virtually the only basis for any economic activity. More than 40 different kinds of species in Iceland are harvested for the commercial purpose and the total annual catch in recent years, up to 2008, has fluctuated around 1.5 up to 2.2 million metric tons.

It would be worth to mention, that according to the statistics from 2008, the most significant species for Icelandic fisheries are cod, which accounts for about 30% of total catch, beside that one, very valuable are also haddock, redfish and pollock which percentage in total catch can be generally estimated for around 15 % of a total catch.

According to the latest news, there has been certain tendency regarding development of property rights in fisheries. Some of the European countries as Denmark, including Faroe Islands, United Kingdom or Ireland, performed the National Quota Management, some of them as Netherlands, New Zealand and Iceland, implemented the ITQs system. It has to be mentioned, that Iceland, where the private property has been generally believed to be fundamental to motivate the economy efficiency and productivity on land, took a leading role in this development and as one of the first countries to introduce individual vessel quotas and individual transferable quotas in major offshore fisheries.

Historical data show that in Iceland, vessel catch quotas were implemented in 1975 in the herring fishery, in 1979 these were made transferable, and in the 1980s started to be used in all fisheries within exclusive economic zone and Icelandic vessels operating outside of this area, creating the current ITQ system.

Historical data show that in Iceland, vessel catch quotas were implemented in 1975 in the herring fishery, in 1979 these were made transferable, and in the 1980s started to be used in all fisheries within exclusive economic zone and Icelandic vessels operating outside of this area, creating the current ITQ system.

Addressing this discussion, it seems to be necessarily to analyze the conventional property rights in Iceland from the legal point of view. Icelandic property rights are neither fixed nor absolute and recognized as sort of privilege which allows to exclude others form some benefits. This concept places the one who holds the rights in certain position in respect to the others who are obligated to follow those rules.

On the other hand, the legal theory states that property right is an aggregate and collection of rights. In this bundle we have to include the authority to control something and to dispose it to the others. The concept behind the implementation of ITQs system lays in the theory that it is a right to fish which is a subject of the concept, not the ownership of marine natural resources itself. It shows to be obvious that no one can posses the rights to the fish unless it has been caught. The natural marine resources are the common property of Icelandic nation.

Current ITQs system has been based on the general provisions of the property rights. It was implemented by the Icelandic Fisheries Management Act of 1990 and changed through next two decades. The last alteration of this document took place in 2006 and provides with the essential features of current ITQ system. Though there might be notice disjunction between the art.1 and art. 4 of the FMA where the first states: “The exploitable marine stocks of the Icelandic fishing banks are the common property of the Icelandic nation.´ while the other seems to negate this statement: “No one may pursue commercial fishing in Icelandic waters without having a general fishing permit.”

This allows to come to the conclusion, that the Icelandic fisheries management system is the closed shop system. Regarding ITQs, this feature puts an emphasis on their exclusive nature. It seems to occur as self evident, that one licensee cannot exclude all others from fishing. Analyzing the document, it can be said that the parties which enjoy a fishing license, in the same time enjoy the exclusive right to run commercial or professional fisheries in Icelandic waters. According to the FMA, current quota system represents shares in total allowable catch. TAC is set annually by the Minister of Fisheries and based on the recommendation from the Marine Research Institute which on the other hand relies on the information from the fishermen and researchers. All commercial fishing activities are subject to these quotas. Currently there are 15 species which are subject to TAC and in the same time to ITQs system. The quota share is multiplied by the TAC to give the quantity which each vessel is concerned during the fishing year in question. This is referred to as the vessels´ catch quota. Permanent quota shares and annual catch quotas are divisible and transferable to other fishing vessels. The allocation of quotas is subject to a fishing fee. Individual enterprises may not control more than the equivalent of 12% of the value of the total quotas allocated for all species, and 12% to 35% for individual species.

The dispute arises when the one starts to think about the transferability of both, TAC and ITQ. The rule says that both of them can be transferred without any restrictions, though the Ministry of Fisheries must agree to distribute them fairly among the geographical regions. After it is done, according to the FMA we can point out the option, where the holder of an ITQ can, wholly of partly transfer its share to another licensed vessel. New regulations implemented in 1990 made it very common to sell the share by private holders, because the extreme amount of money was offered by the big enterprises.

Icelandic ITQs system has or could have, great impact on economic efficiency and what fallows, the maximization of wealth not only among the quota holders but also other citizens who, indirectly benefit from fisheries industry. By implementing ITQs system in Iceland, the interest in the fisheries, coming from big national corporations, was noticed. Those companies, larger entitles different from the Icelandic government, began to actually achieve economy of scale, what means that they were able to give out the product on the lower cost, what means the lower price, because of the progressing massive production and fish processing.

Icelandic ITQs system has or could have, great impact on economic efficiency and what fallows, the maximization of wealth not only among the quota holders but also other citizens who, indirectly benefit from fisheries industry. By implementing ITQs system in Iceland, the interest in the fisheries, coming from big national corporations, was noticed. Those companies, larger entitles different from the Icelandic government, began to actually achieve economy of scale, what means that they were able to give out the product on the lower cost, what means the lower price, because of the progressing massive production and fish processing.

While the ITQs system is being implemented, decision making process starts to depend on the market and current economic situation, rather than being done by non market focused entitles in bureaucratic way, what means faster and more efficient for economy ways. Iceland seems to be very good example for such an observations but similarity might be noticed also in New Zealand, where actually the government’s fishery policy became more efficient when the private sector started to provide with services as opposed to the public ones.

Icelandic ITQ system, shares some of the features with its utopist idea of its impact on economic efficiency. However, there are particular aspects of this dimension, which differ from the theoretical ideal and subtract from its economic efficiency. In the Icelandic ITQ system, which is strongly associated with fishing vessels, only those who actually own vessels with a valid fishing license, can own quotas. What is more, the total holdings of quotas cannot exceed the fishing capacity of the vessel in question. This regulation severely restricts the set of potential holders of ITQs and clearly subtracts from the ability of the quota market to generate the most economically beneficial allocation of those.

The Fisheries Management Act of 1990 implemented a clause setting a limit on the quota holdings of any single vessel, what stated that no vessel can have a larger TAC share than it could catch within the fishing year. Art.13 of FMA states the maximum fishing quota share for fishing vessels owned by individual parties, whether natural or legal persons, or owned by connected parties. Nevertheless, it came to the point that eleven largest firms in Iceland hold about 33% of the demersal quotas and about 32% of all ITQs. Fifty biggest harvesting companies, in 1997 (the last available data) held more than 60% in all ITQs in the beginning of that fishing year.

Icelandic ITQs system increases the economic efficiency by lowering the cost of harvesting, cost of production and price of the out coming product. It allows cheaper labor power and decrease the time spent on the sea by the single fisherman. After actual implementation of ITQs, the human’s migration from small villages in the far north or north – east, down to bigger agglomerations, where the large companies are operating, was noticed. Versions of the ITQs fisheries management have been occurring in Icelandic fisheries since early 1980s and its performance should be considered objectively. The evidence on the economic benefits of the ITQ system is becoming clearer and the TAC for some species will be increased in the near future. The regional impact of the ITQs system shall be taken into account.

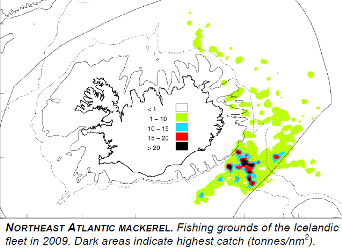

Source: Center of the Icelandic Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture