Iceland has decided to support Canada and Norway in the case against the EU trade ban on seal products. This was decided on a meeting on dispute settlement on the 25th of March. It was also decided on the meeting that Iceland will join the case as a third party member against the EU trade ban.

Iceland has decided to support Canada and Norway in the case against the EU trade ban on seal products. This was decided on a meeting on dispute settlement on the 25th of March. It was also decided on the meeting that Iceland will join the case as a third party member against the EU trade ban.

Iceland is one of six countries where seal hunting is still practiced. The others are Canada, Norway and Russia, which are not EU members states; Greenland, which is a Danish region but has autonomy in its domestic affairs; and Namibia in southern Africa.

This decision of Iceland is in harmony with previous statements of the country. The ban, which was adopted by the EU Council on 27th of July 2009 and came into effect on the 20th August 2010 was also opposed by the Icelandic government in April 2009, where the minister of Fisheries- and agriculture sent a letter to the EU Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries. Worries about impending legislation where mentioned along with other reasons opposing the trade ban. The Icelandic minister for fisheries had also declared his support about the case at the 15th North Atlantic Fisheries Ministers Conference, which was held in Canada in July 2010.

Iceland´s opposition is also shown in the NAMMCO statement on EU import ban on seal products. There, the bans is seen as contrary to international principles for conservation and sustainable management. Along with Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Norway, as well as observer nations to NAMMCO, Canada, the Russian Federation and Japan, reiterated their serious concerns about the EU ban on the import of seal products into the European Union.

Iceland´s opposition is also shown in the NAMMCO statement on EU import ban on seal products. There, the bans is seen as contrary to international principles for conservation and sustainable management. Along with Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Norway, as well as observer nations to NAMMCO, Canada, the Russian Federation and Japan, reiterated their serious concerns about the EU ban on the import of seal products into the European Union.

In the NAMMCO statement it is mentioned that the trade ban ignores and undermines the internationally recognized principles on which conservation and management of marine resources in the North Atlantic are firmly based. It has serious and detrimental consequences for the economies of the many communities dependent on abundant seal stocks across the North Atlantic. Therefore the incorporation of the ban into European Union legislation is said to be a huge step backwards for sustainable development and international trade.

It is further states that the nations cooperating through NAMMCO are committed to promoting the principle of sustainable development in all areas of cooperation in the region, including the sustainable use of seals. Such cooperation is based on mutual respect and recognition of the rights of all peoples to use their resources responsibly and sustainably for their economic development, including the right to benefit from international trade.

It is finalized in the NAMMCO statement that conservation and management of all living marine resources should be science-based and should take account of the marine ecosystems and the interrelation between species, stocks and habitats in which fishing and hunting activities occur.

It is finalized in the NAMMCO statement that conservation and management of all living marine resources should be science-based and should take account of the marine ecosystems and the interrelation between species, stocks and habitats in which fishing and hunting activities occur.

Canada appealed to the European Union the trade ban on seal products to the World Trade Organization. Canadian Fisheries Minister, Gail Shea, has stated that she does not believe the government’s fight for seal hunters will damage other industries that employ more people. Fisheries minister has mentioned that other Canadian industries might be damaged if the country does not take a stand on what she insists is a matter of principle and needs to be ruled on facts, not emotions. A decision from the WTO could take a year or more.

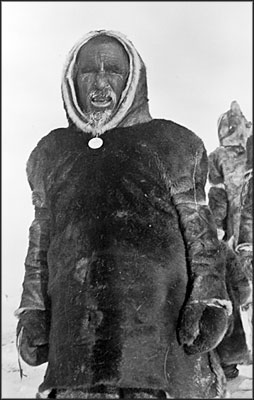

The EU trade ban on seal products has affected Canada’s Inuit community. Despite the fact that the Inuit are exempt from the ban, they no longer have a market for sealskins; a by-product of their subsistence hunt.

A documentary has been made that brings together commentary from Inuit hunters, community leaders and an emotional testimonial from local people.

Seal Ban: The Inuit Impact – Documentary

Sources:

The Icelandic Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture

Another significant aspect of the proposed Icelandic Arctic policy is react against armament in the Arctic region has been raised in the parliament. This point has been discussed to a certain degree in the Althing, where the foreign minister has tried to water down the concerns of direct military confrontation or severe armament. The third significant political aspect of the discussions in the Althing about the policy is the EU negotiation phase and the outcome in Arctic matters for the European Union. Some concerns have been raised that the argument for Iceland as an Arctic coastal state is meant to secure the interests of the EU instead those of Iceland specifically. Even though this concern might be a bit farfetched, it was officially declared by the EU that Arctic matters were the primary gain for the EU with the membership of Iceland.

Another significant aspect of the proposed Icelandic Arctic policy is react against armament in the Arctic region has been raised in the parliament. This point has been discussed to a certain degree in the Althing, where the foreign minister has tried to water down the concerns of direct military confrontation or severe armament. The third significant political aspect of the discussions in the Althing about the policy is the EU negotiation phase and the outcome in Arctic matters for the European Union. Some concerns have been raised that the argument for Iceland as an Arctic coastal state is meant to secure the interests of the EU instead those of Iceland specifically. Even though this concern might be a bit farfetched, it was officially declared by the EU that Arctic matters were the primary gain for the EU with the membership of Iceland.

The report presents the Commission’s recommendations, foremost of which is that governance in the Arctic marine environment, which is determined by domestic and international laws and agreements, including the Law of the Sea, should be sustained and strengthen by a new conservation and sustainable development plan using an ecosystem-based management approach. The Commission believes marine spatial planning provides a workable method or approach to begin implementation of ecosystem-based management. According to the Commission, Arctic governance can and should be strengthened through an inclusive and cooperative international approach that allows greater participation in information gathering and sharing, and decision-making, leading to better informed policy choices and outcomes.

The report presents the Commission’s recommendations, foremost of which is that governance in the Arctic marine environment, which is determined by domestic and international laws and agreements, including the Law of the Sea, should be sustained and strengthen by a new conservation and sustainable development plan using an ecosystem-based management approach. The Commission believes marine spatial planning provides a workable method or approach to begin implementation of ecosystem-based management. According to the Commission, Arctic governance can and should be strengthened through an inclusive and cooperative international approach that allows greater participation in information gathering and sharing, and decision-making, leading to better informed policy choices and outcomes. The Commission recognizes that this Aspen Dialogue has been a preliminary step toward a fuller discussion on the future of the Arctic marine environment. Its major discovery is that a more modern, holistic and integrating international plan is needed to sustainably steward and govern the Arctic marine environment. The Commission has made significant progress in understanding the needs and requirements for action to sustain the Arctic and realizes that in order to implement its recommendations the entire Arctic community must be engaged.

The Commission recognizes that this Aspen Dialogue has been a preliminary step toward a fuller discussion on the future of the Arctic marine environment. Its major discovery is that a more modern, holistic and integrating international plan is needed to sustainably steward and govern the Arctic marine environment. The Commission has made significant progress in understanding the needs and requirements for action to sustain the Arctic and realizes that in order to implement its recommendations the entire Arctic community must be engaged. The Aspen Institute Commission on Arctic Climate Change believes that existing frameworks can be enhanced and new frameworks can be established to improve governance and strengthen resilience in the Arctic marine environment in response to climate change impacts and the need for adaptation readiness. The Commission developed its recommendations against the backdrop of at least three observable strategies currently discussed internationally to strengthen the Arctic Council; expand and strengthen the existing system of bilateral and multilateral agreements; and/or establish a new Framework Convention for Arctic governance.

The Aspen Institute Commission on Arctic Climate Change believes that existing frameworks can be enhanced and new frameworks can be established to improve governance and strengthen resilience in the Arctic marine environment in response to climate change impacts and the need for adaptation readiness. The Commission developed its recommendations against the backdrop of at least three observable strategies currently discussed internationally to strengthen the Arctic Council; expand and strengthen the existing system of bilateral and multilateral agreements; and/or establish a new Framework Convention for Arctic governance.

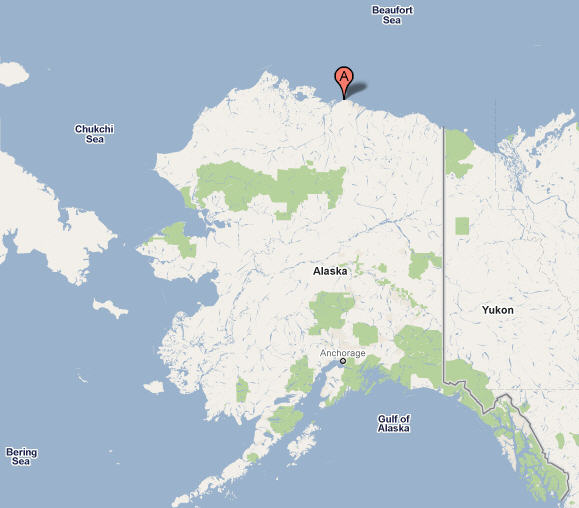

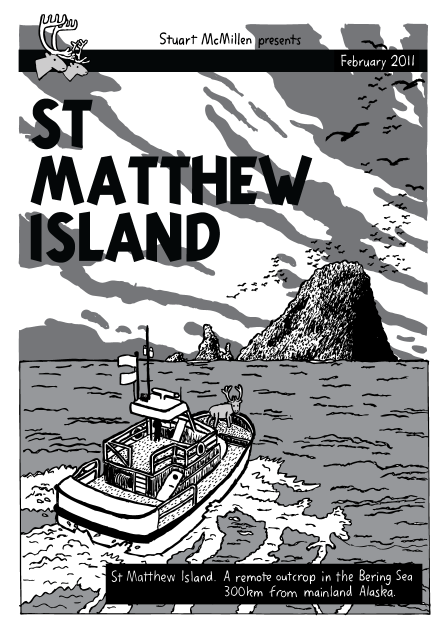

St. Matthew then had the classic ingredients for a population explosion—a group of healthy large herbivores with a limited food supply and no creature above them in the food chain. That’s what Dave Klein saw when he visited the island in 1957. Klein was then a biologist working for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. He is now a professor emeritus with the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Institute of Arctic Biology. The first time he hiked the length of St. Matthew Island in 1957, he and field assistant Jim Whisenhant counted 1,350 reindeer, most of which were fat and in excellent shape. Klein noticed that reindeer had trampled and overgrazed some lichen mats, foreshadowing a disaster to come.

St. Matthew then had the classic ingredients for a population explosion—a group of healthy large herbivores with a limited food supply and no creature above them in the food chain. That’s what Dave Klein saw when he visited the island in 1957. Klein was then a biologist working for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. He is now a professor emeritus with the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Institute of Arctic Biology. The first time he hiked the length of St. Matthew Island in 1957, he and field assistant Jim Whisenhant counted 1,350 reindeer, most of which were fat and in excellent shape. Klein noticed that reindeer had trampled and overgrazed some lichen mats, foreshadowing a disaster to come. Other work commitments and the difficulty of finding a ride to St. Matthew kept Klein from returning until the summer of 1966, but he heard a startling report from men on a Coast Guard cutter who had gone ashore to hunt reindeer in August 1965—the men had seen dozens of bleached reindeer skeletons scattered over the tundra.

Other work commitments and the difficulty of finding a ride to St. Matthew kept Klein from returning until the summer of 1966, but he heard a startling report from men on a Coast Guard cutter who had gone ashore to hunt reindeer in August 1965—the men had seen dozens of bleached reindeer skeletons scattered over the tundra.

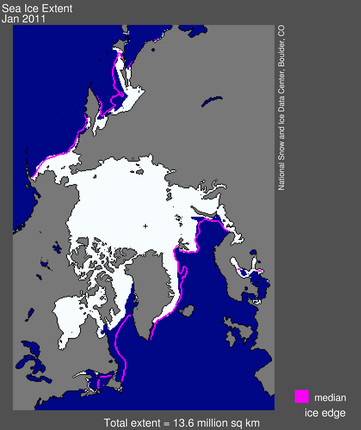

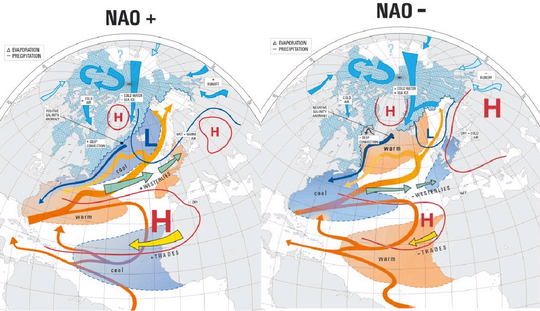

The oscillation exhibits a “negative phase” with relatively high pressure over the polar region and low pressure at midlatitudes (about 45 degrees North), and a “positive phase” in which the pattern is reversed. In the positive phase, higher pressure at midlatitudes drives ocean storms farther north, and changes in the circulation pattern bring wetter weather to Alaska, Scotland and Scandinavia, as well as drier conditions to the western United States and the Mediterranean. In the positive phase, frigid winter air does not extend as far into the middle of North America as it would during the negative phase of the oscillation. This keeps much of the United States east of the Rocky Mountains warmer than normal, but leaves Greenland and Newfoundland colder than usual. Weather patterns in the negative phase are in general “opposite” to those of the positive phase, as illustrated below.

The oscillation exhibits a “negative phase” with relatively high pressure over the polar region and low pressure at midlatitudes (about 45 degrees North), and a “positive phase” in which the pattern is reversed. In the positive phase, higher pressure at midlatitudes drives ocean storms farther north, and changes in the circulation pattern bring wetter weather to Alaska, Scotland and Scandinavia, as well as drier conditions to the western United States and the Mediterranean. In the positive phase, frigid winter air does not extend as far into the middle of North America as it would during the negative phase of the oscillation. This keeps much of the United States east of the Rocky Mountains warmer than normal, but leaves Greenland and Newfoundland colder than usual. Weather patterns in the negative phase are in general “opposite” to those of the positive phase, as illustrated below.

Owing to their traditional local diet some Arctic peoples receive high dietary exposure to mercury, raising concern for human health. Arctic wildlife also exhibit mercury levels that are above thresholds for biological effects raising concern for the environment. The Arctic is a remote region, far from major human sources of mercury releases. Despite this, a substantial amount of the mercury is carried into the Arctic region via long-range transport by air and water currents from human sources at lower latitudes. This situation calls for urgent global action to reduce mercury emissions.

Owing to their traditional local diet some Arctic peoples receive high dietary exposure to mercury, raising concern for human health. Arctic wildlife also exhibit mercury levels that are above thresholds for biological effects raising concern for the environment. The Arctic is a remote region, far from major human sources of mercury releases. Despite this, a substantial amount of the mercury is carried into the Arctic region via long-range transport by air and water currents from human sources at lower latitudes. This situation calls for urgent global action to reduce mercury emissions. Globally, about 2000 tons of mercury are emitted to the atmosphere each year as a result of human activities. A similar amount is emitted each year from natural sources. In addition, mercury that has accumulated in soils and ocean waters can be re-emitted to the air. This means that mercury contamination, a large part of which is derived from human activities, is recycled in the environment. Studies indicate that if no action is taken, mercury emissions from human sources are likely to increase in the next decades, but if implemented, existing technologies could significantly reduce emissions. Mercury is transported to the Arctic by air currents (within a matter of days) and ocean currents (that may take decades) and by rivers from human activities in lower latitudes. Coal burning outside the Arctic Region is the most significant source of mercury that can reach the Arctic via long-range transport. The chemical form in which mercury is released, and the processes that transform mercury between its various chemical forms are a key in determining how mercury is transported to the Arctic and what happens to it when it gets there.

Globally, about 2000 tons of mercury are emitted to the atmosphere each year as a result of human activities. A similar amount is emitted each year from natural sources. In addition, mercury that has accumulated in soils and ocean waters can be re-emitted to the air. This means that mercury contamination, a large part of which is derived from human activities, is recycled in the environment. Studies indicate that if no action is taken, mercury emissions from human sources are likely to increase in the next decades, but if implemented, existing technologies could significantly reduce emissions. Mercury is transported to the Arctic by air currents (within a matter of days) and ocean currents (that may take decades) and by rivers from human activities in lower latitudes. Coal burning outside the Arctic Region is the most significant source of mercury that can reach the Arctic via long-range transport. The chemical form in which mercury is released, and the processes that transform mercury between its various chemical forms are a key in determining how mercury is transported to the Arctic and what happens to it when it gets there.

The Assessment on Mercury in the Arctic documents how mercury continues to present risks to the health of Arctic human populations and wildlife. A particular concern is the fact that in large areas of the Arctic mercury levels are continuing to rise in some Arctic wildlife despite reductions in emissions from human activities over the past 30 years in some parts of the world. Based on the results of the assessment the Arctic Council confirms the need for concerted international action if mercury levels in the Arctic and in the rest of the world are to be reduced. The AMAP 2011 assessment will be presented at the Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting to be held on 12 May 2011 in Nuuk, Greenland.

The Assessment on Mercury in the Arctic documents how mercury continues to present risks to the health of Arctic human populations and wildlife. A particular concern is the fact that in large areas of the Arctic mercury levels are continuing to rise in some Arctic wildlife despite reductions in emissions from human activities over the past 30 years in some parts of the world. Based on the results of the assessment the Arctic Council confirms the need for concerted international action if mercury levels in the Arctic and in the rest of the world are to be reduced. The AMAP 2011 assessment will be presented at the Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting to be held on 12 May 2011 in Nuuk, Greenland.

According to the Icelandic fisheries portal, at least 12 species of whales, dolphins, and porpoises occur regularly in Icelandic waters and 11 other have been recorded more sporadically. Out of those 23 species that are recorded around Iceland, two are scientifically assessed and annual catch recommendations based on that, fin whale and minke whale. The Icelandic Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture considers whaling as sustainable and the Icelandic whaling policy is based on precautionary approach. This means that the whale stocks benefit of the doubt. In context with whaling, a quota is issued where number of whales captured does not exceed future sustainable development of the stock.

According to the Icelandic fisheries portal, at least 12 species of whales, dolphins, and porpoises occur regularly in Icelandic waters and 11 other have been recorded more sporadically. Out of those 23 species that are recorded around Iceland, two are scientifically assessed and annual catch recommendations based on that, fin whale and minke whale. The Icelandic Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture considers whaling as sustainable and the Icelandic whaling policy is based on precautionary approach. This means that the whale stocks benefit of the doubt. In context with whaling, a quota is issued where number of whales captured does not exceed future sustainable development of the stock. appreciably. An aerial survey conducted in coastal Icelandic waters in 2007 showed lower abundance estimates than previous surveys, or 10 700 and 15 100, depending on the method of analysis. A survey conducted in 2008 showed much higher densities, indicating that the unusually low densities in 2007 were due to a temporary shift in distribution within the population area. Based on a stock assessments conducted by the Scientific Committees of NAMMCO and the IWC, it was recommend by the Icelandic Marine Research Institute that annual catches of common minke whales from the Central North Atlantic stock do not exceed 216 animals in the Icelandic continental shelf area.

appreciably. An aerial survey conducted in coastal Icelandic waters in 2007 showed lower abundance estimates than previous surveys, or 10 700 and 15 100, depending on the method of analysis. A survey conducted in 2008 showed much higher densities, indicating that the unusually low densities in 2007 were due to a temporary shift in distribution within the population area. Based on a stock assessments conducted by the Scientific Committees of NAMMCO and the IWC, it was recommend by the Icelandic Marine Research Institute that annual catches of common minke whales from the Central North Atlantic stock do not exceed 216 animals in the Icelandic continental shelf area.

The Saami languages also categorize snow according to texture and context. For example, words used in connection with skiing and reindeer husbandry are different, even though the snow would be the same. It is also interesting to notice that even though Saami and Finnish are related languages and many of the words for snow in Saami sound familiar to Finnish speakers, the Finnish language itself only has three different official words for snow. The Saami word vahtsa means one or two inches of new snow on top of old snow. New wet snow is called slahtte and falling rain mixed snow slabttse. Falling wet snow lying on the ground is called släbtsádahka or släbsát. Skilltje, bulltje and tjilvve are words for snow and ice that fall on objects, reindeer moss and trees. Large lumps of snow hanging on the ridge are nearly always called bulltje. Åppås on the other hand is virgin, clear snow.

The Saami languages also categorize snow according to texture and context. For example, words used in connection with skiing and reindeer husbandry are different, even though the snow would be the same. It is also interesting to notice that even though Saami and Finnish are related languages and many of the words for snow in Saami sound familiar to Finnish speakers, the Finnish language itself only has three different official words for snow. The Saami word vahtsa means one or two inches of new snow on top of old snow. New wet snow is called slahtte and falling rain mixed snow slabttse. Falling wet snow lying on the ground is called släbtsádahka or släbsát. Skilltje, bulltje and tjilvve are words for snow and ice that fall on objects, reindeer moss and trees. Large lumps of snow hanging on the ridge are nearly always called bulltje. Åppås on the other hand is virgin, clear snow.